Listing and identifying flora and fauna is fun, but naming and objectively labeling is an intellectual, ordering sort of activity. For me, the essence of life, the magic of life, is not found through a detached vantage point; it’s felt by connecting, within and through our relationships with other beings. It’s a heart-centered experience. Through the ebbs and flows of life, connections old and new keep us whole. They diminish my singular importance and yet enhance it by making “me” part of life’s larger, unfolding web. They empower, ground, and sustain us.

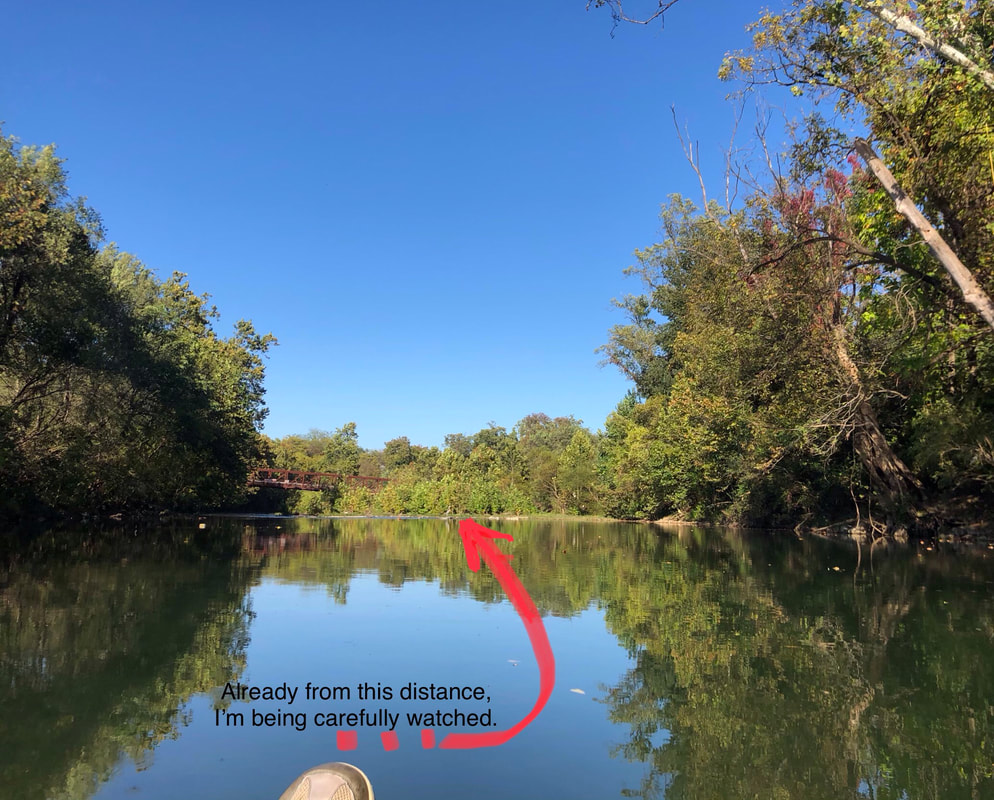

Beyond this vast menagerie of beings I met on the river the last six months, usually watching warily from a distance were the great blue herons. A pair, I assume, since other than at the nest or when courting, they rarely hang near each other. As the summer heat moved in, the smaller herons moved out (likely part of their regular migration patterns), and the great blues became more obvious. Covid-19 restrictions had encouraged many more folks to be in and near the river this spring and summer, and these cautious birds keep clear of noisy or boisterous humans. They feed quietly spearing their prey along the banks, so it makes sense; we mostly just interrupt their survival. However, as back to school studies and cooler temperatures arrived, and the river became less “peopled” the herons began to frequent the section I float more regularly.

As with humans, developing a rapport takes time. I’d been floating in my tube pretty consistently this year along the same route—May through August nearly every day and during a month of severe July heat often twice a day. My routine has since tapered off with the cool weather. But I feel very fortunate to have encountered the great blues regularly, and, I feel, to have been allowed to come ever closer over the months, slowly accepted as “safe.”

I remain captivated by these majestic birds; they intrigue and inspire me. We’re generally the largest mobile beings along the riverway. And each in our own way, elsewhere—perhaps because of my height I relate to not needing to announce myself in public settings, and am attracted to their willingness to observe with a mostly quiet presence. The introverted part of me relates to their caution, solitary foraging, and decisive responsive behavior. I appreciate their patience, their keen sight, and lightning reflexes. I strive to emulate their ability to focus intently on what’s within their reach, and yet maintain an awareness of everything on the river. They can appear awkward and in the next second embody graceful elegance. Once they’ve attained flight, watching their slow, powerful, efficient strokes lift them skyward makes my spirit soar.

When mature adults (they can live 15 years) depart from a setting, they’ll usually fly around a bend well beyond sight—I assume so they can safely reset their sensory radar in a new location that’s “neutral” so any changes or intruders will trigger their alert systems. As the local pair and I became more familiar, a “trust” slowly yet steadily developed and I was allowed to get nearer. As with any friendship, there were missteps, at times I was insensitive to them, other times a loud sound from something beyond me frightened them off. Though I’ve gotten pretty good at spotting them in the distance, oftimes I simply didn’t even notice them until my hand splashing in the water prompted them to take flight. I wonder with regret how often I’ve been selfishly wrapped up in my internal concerns and callously caused a friend to feel a need for space... Seems I’m still learning that in order to honor respectful boundaries, one needs to keep assumptions in check and be aware and sensitive beyond one’s self.

Coming to know a young adult great blue heron has been a highlight this fall. I’ve watched this emerging adult react to me, seemingly “figuring me out.” As I approach, clicking the same sound over several weeks, it seemed unsure what to make of me and tried out a variety of responses. Sometimes it took flight, but either still learning heron survival etiquette or simply unsure how much of a threat I was, it would fly a short distance downriver, and so we’d repeat the scenario over several times. On other occasions it would straighten its posture, point its beak skyward and hold still. This evolved technique works against predators effectively merging it with tall grasses and saplings and to a degree making it invisible — but not quite to a human floating by, which always made me smile. Sometimes, as I made chattering sounds floating toward it, it would cock its head to either side, intrigued. I’ve seen it fly off, land in the shallows, eye me, then suddenly, like a young human distracted by a text ding, notice something at its feet and forget about me altogether — we all know a mature adult honors priorities and keeps distractions in check ; ) .

Friendships with beings of all ages are an invaluable gift. It’s a beautiful, vitally important thing to be able to connect to others. I’m so grateful these herons graced and buoyed my life throughout this challenging COVID-19 year, and my human friends as well. Whether distanced by other priorities, disrupted by my own blunders, or interrupted by circumstance, I hope the sincere and good aspects of our relationships are what hold fast. May we all (herons and humans, pre and post-pandemic) retain mostly the joyful, supportive memories of our shared experiences as we soar beyond the breaks bound to occur through the seasons of life.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed