Within a short time, three other siblings decided we could fit it in and would join her. I was keen to go; my intuition compelled me. It wasn’t that Helen needed me (or us) to support her on this journey, but I suspected it’d be an emotional trip for us all, as our mother had passed last year as well. I’ve come to learn we’re a bit rare, in that our family enjoys being together (including the fifth sib, and all partners, who weren’t able to come). We don’t live in close proximity, so we always look forward to being together. While the trip to the crash site was heavy, the adventure was mostly joyous and even percolated with laughter. It was a brief four-day excursion, yet brimming with so many feelings.

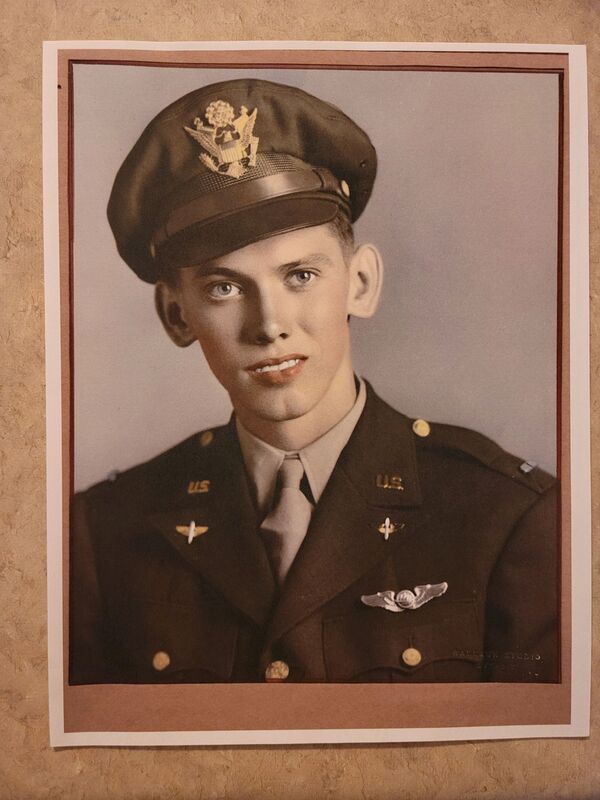

My Uncle Jan, “Johnny” to his six sisters, was the only son in the family. My mother was his closest sibling, and referred to him as her big brother. They walked to and from school together. Two years apart in age, he “looked out for her.” He was bright, “good at math”, kind, helpful, and had a gentle sense of humor that put others at ease. By all accounts he was adored by everyone. He enlisted at 18 and spent a year in flight training in the fledgling, not yet named branch of the Army now known as the Air Force. His training class began in Texas and he was stationed in Casper, Wyoming in the fall of 1944.

We learned of the crash site only in the last decade. His family was informed of his death, like too many others during war, by a knock on the door. It’s a hard to comprehend the reality that more American planes (over 5,000) crashed in training in the US than were shot down overseas in the years 1942-45. We have copies of handwritten letters Uncle Jan wrote to home, right up to a few weeks before his death. Reading them tugs at one’s heart, as he teases about his sisters and humbly shares about his achievements and hopes to his parents during the severe global challenges of 1944. They confirm all the attributes I listed above. It’s impossible to imagine the pain of my immigrant grandparents and aunts getting such news that October day. It was also difficult for me to not equate his affable and beloved personality with that of my brother in law Scott, whose colleagues we met on the trip, who repeatedly pointed out all the ways he’d nurtured the growth of everyone with whom he came into contact in the USGS.

My mother could barely discuss the incident that took her brother, and for the rest of her life became uneasy whenever she heard “Taps”. Though she was 17 and the family was given details about the crash (six of ten in the crew survived), uncharacteristically her sharp memory blocked out what state it had happened in. Through the help of a friend (John Hammill) I was able to learn how to access the military records, and slowly learned the crash occurred near a small town in the farmlands of northern SD. Somehow, this information was important to me and I shared it with my family several years ago.

About the same time, my brother in law Scott (also a pilot) was promoted to work with states in the same region. He happened to have a conversation with a friend who was into “Geocaching”. Through some unknowable karmic plan, his friend discovered that in 2010 a plaque honoring the crew and marking the site had been installed. Suddenly, we had a concrete physical place-holder for a lingering, decades old, sad family mystery. A quick scan of maps revealed that Lemmon, the closest town (pop. 1100) is about 4 hours from the nearest major airport, and for me a drive was a 1600 mile, 25 hr. trip. Not an easy trek. I stored the idea of a visit away as a “someday” journey. A few weeks ago my sister brought that day forward.

We all flew to and met in Minneapolis/St. Paul. From there it was a four hr. drive to Jamestown, ND where my nephew is working. Then another 3 hours south to Lemmon, SD. The landscape, on the edge of the famed Badlands, is rolling green hills. Though scenic, it felt conspicuously sparse. There are croplands, and cattle, but seemed to be very few homesteads. Perhaps because of this it held a strange presence. One gets the impression the farming must be on a mega scale. We quickly were gaging distances between gas stations.

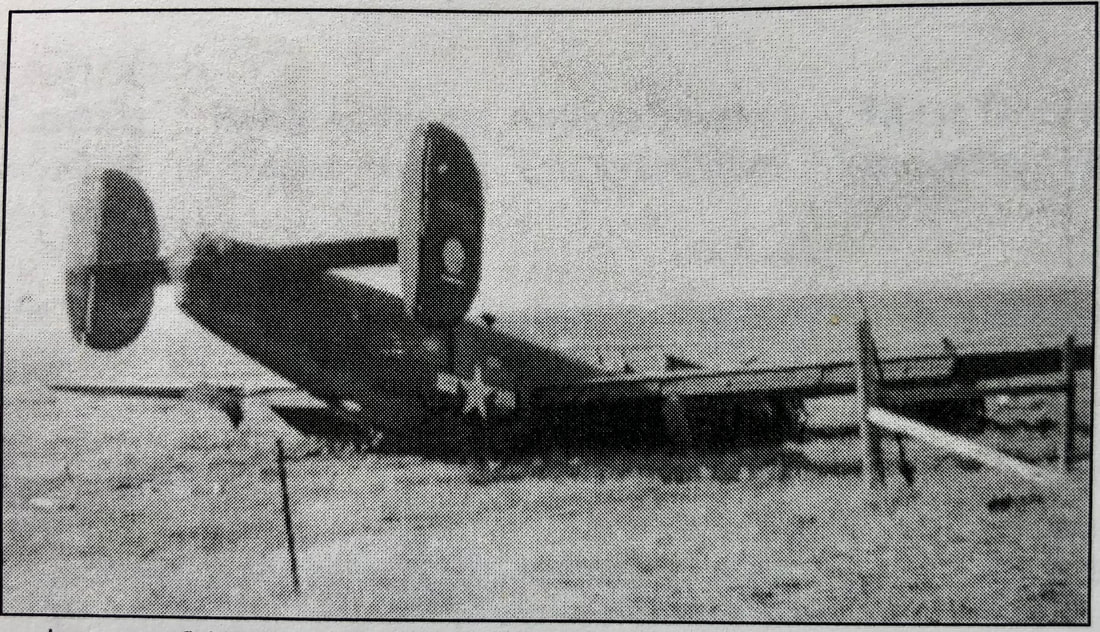

Following the trail of the creation of the plaque, eight years ago I found and spoke on the phone to the octogenarian who, with his VFW group, had funded and gotten it installed. He’d actually heard the plane go down that night in 1944 when he was a young boy, as the engines were alternately back-firing and one caught fire as the pilots struggled to regain control in those fateful last minutes of flight. Three crew members parachuted to safety. Another failed to open his chute in time. Another perished after jumping when the plane was too low. My uncle was the navigator, and by the account from the pilot, had stayed on (typically) attempting to assist and only prepared to leave when ordered. Sadly, he had on his chute but never jumped, as his body was found 50 feet from the crash, bombay doors open. Another crew member died on impact. Miraculously three lived through the crash, the pilot and copilot survived despite not having their safety belts on “we braced our legs against the cockpit dash…and the plane skidded on its belly.” It slid over 200 yards, knocking off all four propellers before tipping on its nose. A local farmer helped extricate a gunner from the wreckage.

We knew we needed more directions to locate the plaque, so were happy to learn there was a public library in town and stopped in. Not only were we able to pull actual newsprint papers with local accounts of the crash, the lone librarian said “Oh yes, we have a file,” and pulled a Manila folder from a cabinet. It was filled with crash photos, copies of documents, paperwork, images of the plaque, and a hand-drawn map to the site. Stunningly, there within the file were also emails from myself to the farmer who’d heard the crash and initiated the plaque, forwarding another from my brother in law Scott, corresponding with his friend when we were first verifying the plaque ten years earlier. The librarian also mentioned that old farmer was her great uncle.

With a sense of destiny we headed down the state roads toward the plaque. The gray, rainy day somwhow enhancing the mood of this hauntingly beautiful landscape. We followed the map to single lane dirt roads, marked our way to within a few miles, but reached a point where the scribbled “landmarks” weren’t helpful. We had longitude and latitude coordinates, so my math-minded sisters in the back seat tried to guide us with those, but Google wasn’t available. We called the old farmer, but we had no cell service. The emptiness of the land and sheds matched our frustration. We saw one sign at one adjoining road for “Storm Ranch,” but there was no way to know how many miles off it might be.

We knew we were to cross a gate but hesitated to go anywhere on foot, especially when further along a sign declared “PRIVATE PROPERTY. No hunting. Do not trespass! Do not fuck around with us!” There were no homesteads visible. The few buildings we came upon seemed abandoned. Doubt crept in as we sensed we might have to accept we’d not find it. My brother, driving, said several times “let’s try just one more hill…” Having driven seven hours beyond our flight from Minneapolis, we were determined to push on. We reached an impasse and reversed course, heading back to the Storm Ranch sign. After cresting a few more hills, my phone suddenly worked and I reached the old farmer’s home. A woman cautiously answered and said he was out getting the mail. I tried to convey I was not selling anything, and trying to find the plaque, but we were cut off — possibly intentionally.

We pressed on. Another mile and we found a cluster of farm buildings and a small ranch house. Pulling into the long drive a mangy dog appeared, while another barked from within an off-road 4-wheeler. I hesitatingly opened my car door and tried to calm the dog, when an older woman came out of the garage. I greeted her (the line from the Dylan song “by the dirt ‘neath my nails I guessed [she] knew I wouldn’t lie” in my mind). My siblings climbed out as her husband, still in stockings, stepped onto the porch. “I know about the plaque. It’s on our property!” We had a delightful chat, learned the previous winter had tested even their grit, “we couldn’t get the house to keep warm—one day it got to -56°!” They provided explicit directions, a few miles back to the road we had been on, and through a closed gate. “It’s good thing its been raining, I worry visitors’ low cars might catch the fields on fire” Ms. Storm had told us. We opened it and followed the tire tracks gently nudging cattle (cows, calves, and bulls) off our just visible route. Another mile and we parked, as suggested, and walked the last half mile.

The gray clouds still hung, but the rain had graciously stopped. The wind seems constant in these Dakota hills and had a strong presence. We walked through thistle, sagebrush, low grasses, and cow patties. Finally a small, discrete metal plaque, mounted to two metal posts along a fence came into view. Off in the distance was an old homestead (or schoolhouse?). We’d made it. It felt like an achievement, but our journey really masked a deeper one.

.

As we gazed out, the wind steadily waving the grasses, we all went a bit inward. My sister called us to a group hug, and we all felt a few tears as we considered our mother and her dear brother. I knew from the outset we were bringing healing closure to an open wound my mother and her family had borne for over 75 years. No one in our large extended family had ever been to this site. I thought about the illogical route which extended over many years, and through formerly unconnected lives, that had led us here. I felt my uncle Jan, my mother, and her parents, and all her siblings, all no longer “alive”, were palpably “there” with us.

Although time may be a useful conceptual tool, it seems to me its just an abstract idea. I don’t feel the energy that is consciousness, the unnameable, underlying force behind all we experience, is just a concept. In arriving at this site, by holding space through being there, we somehow reconnected to and were bathed in this deeper reality, this indescribable thing we all are part of. We were immersed in it via a sweet and kind young man, barely out of high school: a son, a brother, a friend, an uncle, who (like countless others in the human—and I feel, nonhuman—story) had unselfishly placed himself in circumstances with a genuine desire to help others. In doing so, his life, as our culture frames it, had come to an end. I see it as a transition, a homecoming of sorts, on this simple yet vibrant field. His energy merged with the soil, sage, and wind. And now with ours as well. I collected some dirt and sage from this hallowed ground, took in some deep breaths, and we departed, carrying forward some of the presence of this at once unique and yet utterly common place. A timeless moment in a beautiful experience in which we all share.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed